Biography

An interview by Money Maker covering Richard’s story from his beginnings in rural Australia to an angel investor

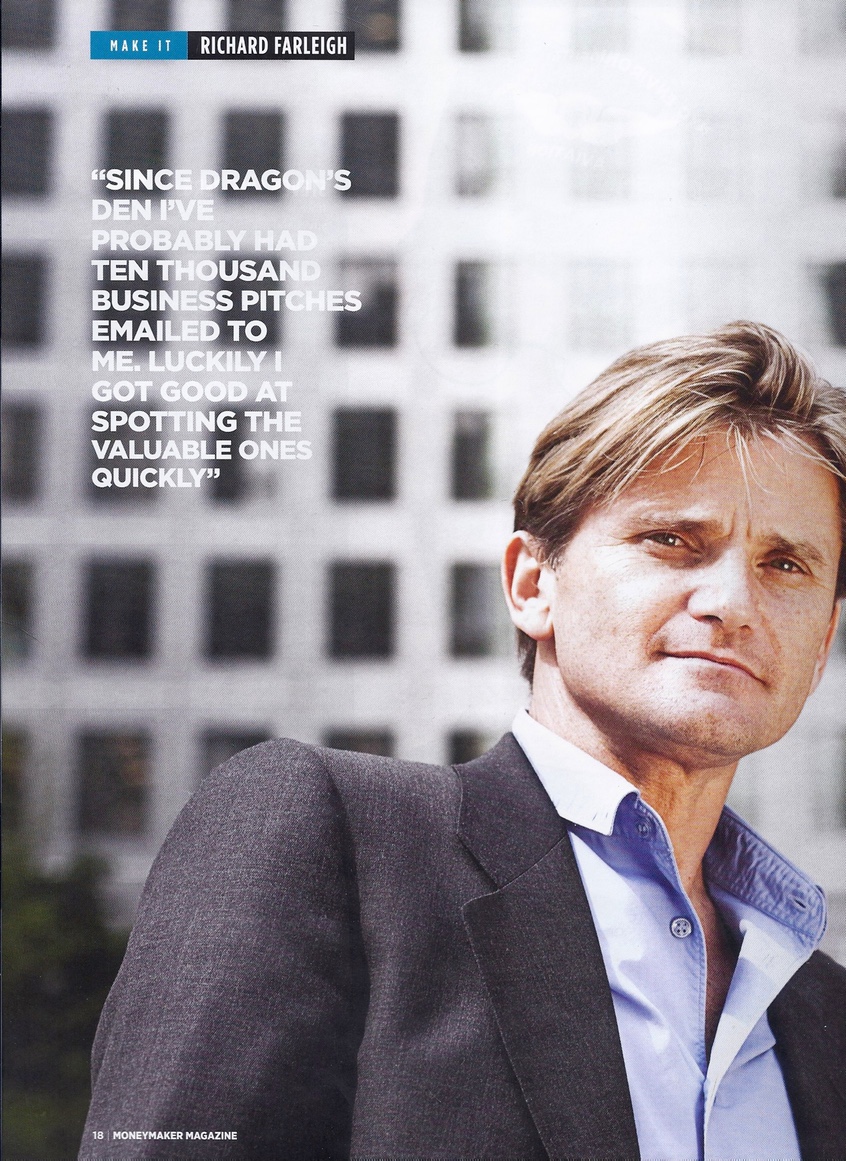

When the smiling and likable Australian new guy appeared on Dragons Den back in 2005, entrepreneurs entering the den had to double take. For, far from the punning passive-aggressiveness that had become the normal dialect of the millionaire investors to the nervous pitchers, Richard Farleigh appeared supportive, encouraging and interested in the people standing in front of the cameras. Indeed, where some fellow dragons would sail close to mockery at times, Farleigh seemed like he was on the pitching entrepreneurs' side, and even if he didn't invest would find time to hand out constructive criticism of where to improve.

Times change, and now eight years on the other dragons appear to have come around to the Australian's way of thinking, with the puns still there, but the acid tongues slightly less prevalent. But behind the nice guy exterior there lurks a steely and wildly successful business person, with a track record that would be the envy of anyone to exit the infamous Den, investor or entrepreneur.

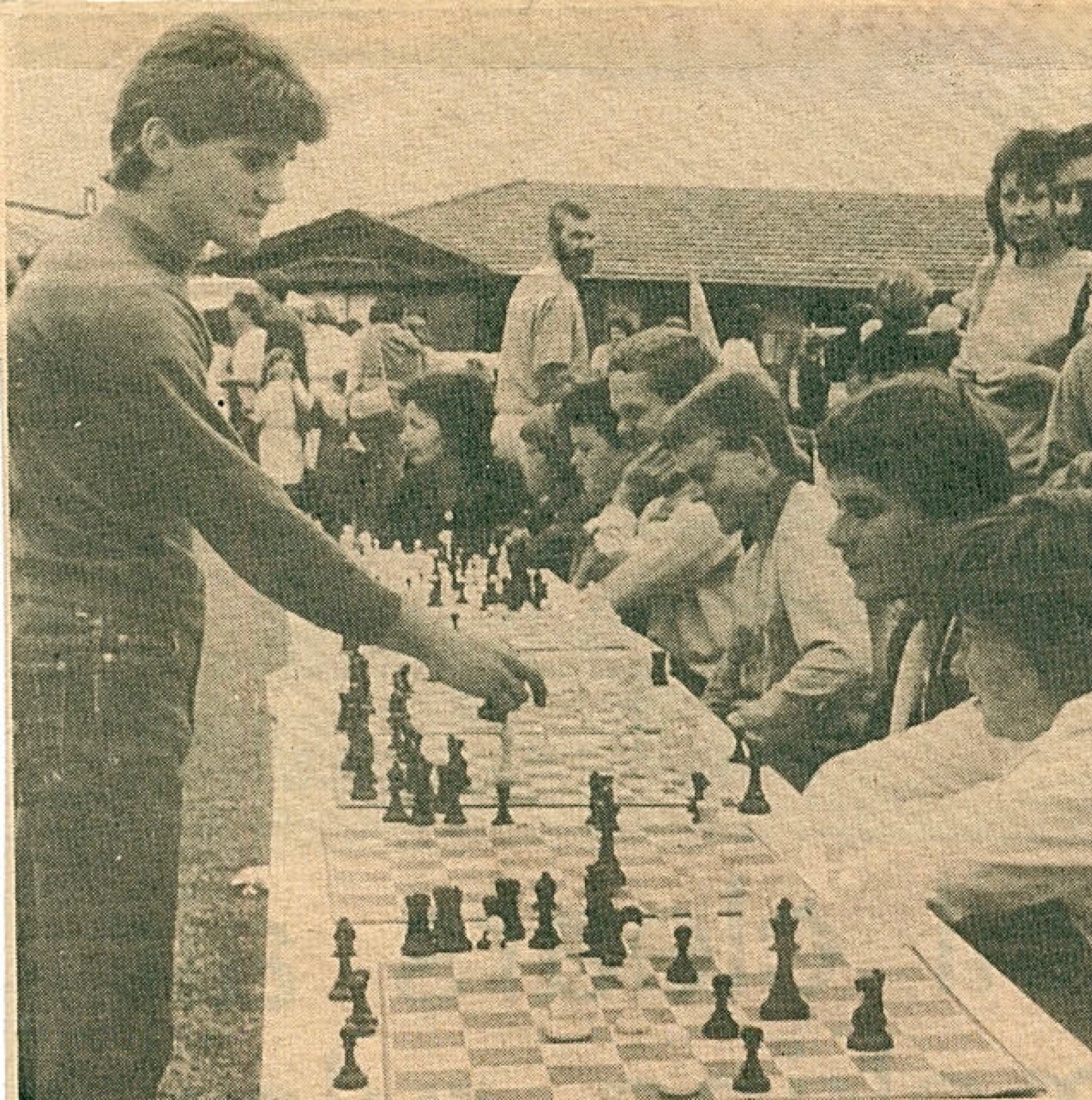

Farleigh grew up in a troubled foster family, and cites the stigma he faced from being seen as "backward" in classes as the inspiration that led him to the game of chess. Here, away from the schoolyard bullies and ineffective teachers, he could enter his own world, where he could learn the rules and linear behaviours of the game board, and his opponents. He quickly began beating every other child, and it wasn't long before not only was he beating every adult player he faced too, but was taking part in high level competitions.

"Chess was the first thing I was good at", he recalls. "When I was behind at school and life was a bit tough, being a good tournament chess player as a junior gave me a lot of confidence. It really helped me and taught me how to think.

There are not many things you do when you're fifteen that require you to sit down for four hours and concentrate and focus - I certainly don't see teenagers doing that in any other activity, not computer games, certainly. There's nothing that teaches you to concentrate that hard, and I learned to think, probably for the first time."

When he realised he wouldn't ever reach the very top of the chess game he shifted his focus to his university studies, and found his new found analytical skills made him a very effective and in-demand mathematician, capable of seeing structures and patterns where others saw chaos. Soon he was picked up by an investment bank, where his numerical mind ran into overdrive, allowing him to become the bank's most successful trader of all time. Then, in his early thirties, Farleigh was head hunted by a hedge fund in the tax haven of Bermuda, where he again excelled, enabling the star trader to retire at just 34 years of age.

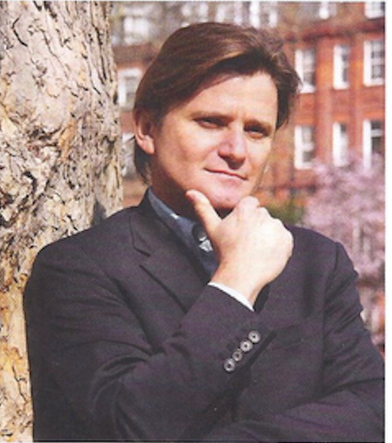

It was at this point that Farleigh the trader turned into the entrepreneur. He spent a few months of his premature retirement racing his Ferrari around his new home of Monaco, before realising the futility of trying to force happiness.

He soon started investing in startups, and quickly found himself with equity in over fifty companies, before he first got the real entrepreneur bug when he had the opportunity to redevelop the old French embassy, Home House in London - one of the World's 100 most endangered buildings. He poured £2 million of his own cash into the project, creating one of the Capital's most desirable private members' clubs.

It was shortly after that the BBC called about the spare seat on the investor panel, after Doug Richard left the show. It's an experience Farleigh has no regrets about taking. "When I got the call I had the luxury of already having seen it on television", he remembered. "I was impressed with it, as it cut across all demographics of genders, ages, and social and educational backgrounds. It had a fantastic spectrum of viewers, so I thought we could do some good. I also felt it was reality TV at its best, because those conversations you see are pretty well what I do on a day by day basis - I thought, 'wow, they've actually managed to capture the real essence of doing business deals.

A successful two year stint on the show followed, with the investor leaving in 2007 to continue with both his own investments and start-ups. One of the most interesting things about Farleigh is his almost boyish excitement when talking about his new ventures. He has a world-class track record of backing successful ideas, and maximising them, but even with over 80 start-ups under his belt he still talks of a new one like a first time entrepreneur, full of energy and anticipation.

"I like disruptive companies, disruptive ideas, things that change the way people do things", he says, rapidly. "If I was just making paper clips and I could just make them ten per cent cheaper that would be a fantastic business, but I wouldn't find it that exciting. It's not a business that would attract me, something that competes on price. I'm much more interested in something that competes on product - that has a brand new type of product, and because of that there's a bit of excitement."

Does Farleigh think this is a great time to be an entrepreneur, in the current climate?

"I LIKE DISRUPTIVE IDEAS, THINGS THAT CHANGE THE WAY PEOPLE DO THINGS. I'M MUCH MORE INTERESTED IN SOMETHING THAT CAN COMPETE ON PRODUCT THAN PRICE”

"Yes and no. It's clearly very difficult for entrepreneurs at the moment, and the issue at the moment is funding, obviously. I see this a lot from the flip side too, as I've taken nearly twenty companies to the AIM market, because for a while my main goal was to develop early stage companies to the point where they can be listed on the stock market. Thes valuations on AIM at the moment are very low, so what that means is for an investor where are you going to put your money? You can put it in a brand new start-up, or you can put it into something which is five to ten years of balance from that point, for not far off the same cost. It's safer in many instances to invest in the later stage company, which is already even listed, than to take a big bet, a big risk, on an untested new company.

"However, there are benefits of the recession to entrepreneurs. When you start a business at the moment, there's less competition, as it's not just your company which is finding funding difficult - it affects everybody. And, if you're trying to expand a small business and you want to buy out other businesses, the valuations are lower, so acquisitions are also good right now. It's about how you look at it."

What does he recommend that entrepreneurs do to combat the funding gap?

"Well there's no easy answer. I think what it means is that entrepreneurs have to be at the top of their game anyway, but in this environment they have to be even better. It's also about choosing the right projects. I always think of start-ups as research projects, and really what you're doing in the first year is just testing the context, because no one really can tell you if an idea is going to work or not. You can have Bill Gates or Warren Buffett sitting there and even then no-one can know if an idea is a goer. It's a trial and error process.

"I advise entrepreneurs to spend the minimum amount of money they can on finding out the most amount of information, and in a recession like this, where there's not much funding, things take twice as long and cost twice as much as you expect. It's a bit like a house renovation. So, given that it's a particularly tough environment, I think people have to be very careful on their costs and be realistic about their revenue. I've done countless start-ups and I've never seen a business plan hit projected targets, so you have to be ready for that."

Does he feel his analytical nature, learned from thousands of chess games in his youth, has given him an extra special ability to predict which businesses will succeed?

"Chess is a great game and has a lot of applications in the real world, but its weakness is that there's very little randomness in chess, and there is a lot of randomness in both the markets and business. When I went into financial markets and then onto business I had to abandon some of the things that chess had taught me because I realised that in business a good idea can fail and a bad idea can succeed, whereas in chess that's not the case - a good idea won't fail and a bad idea should fail. I'm sure I've had businesses which have worked which I wouldn't back again, because I realise now the odds were against it. And on the other hand I've had some good businesses which could well have worked, but we just had a bit of misfortune.

"I hate the word 'luck' - it's a bit flippant. Chess doesn't teach you that. Chess teaches you there's no such thing. I had to learn that the world of business is a bit more like backgammon. You can play the right moves but you don't always win, so you have to handle the losses. You have to learn how to deal with backward steps."

And how does the serial investor and entrepreneur handle losses?

"SPEND THE MINIMUM AMOUNT OF MONEY TO FIND OUT THE MOST INFORMATION. THINGS TAKE TWICE AS LONG AND COST TWICE AS MUCH AS YOU ЕХРЕСТ"

"It's funny. Obviously, I've launched eighty or so start-ups, but each one has been heartfelt, and there's always an element of disappointment if it doesn't work out. You have the hopes and dreams when a company starts, and there's always a lot of disappointment if it doesn't work. I suppose I've had enough successes that I'm philosophical about it, and I suppose from when I used to run a proprietary trading desk, like a risk taking desk for an investment bank, I'm very used to handling losses."

Since appearing on Dragons' Den Farleigh is now pitched to all of the time, wherever he goes, but remains good humoured about it.

"Since the show I've had probably ten thousand email pitches come in, and you have to get good at spotting the valuable ones. The best ones say what is unique about their product quickly. Forget sob stories, just tell me, in the very first sentence, that the world's supply of tin is running out, therefore we have a mine which is going to increase supply by 50 per cent. Tell me the problem and your solution in the very first sentence. It's got to leap off the page and grab you.

"I'm looking for people with that little 'X' factor, even though it's only in writing Obviously, it's easy in meeting someone to see if they've got it, because I've got to like and trust the person. A lot of it is about trying to read the pitcher, and it's not always about the product, so I'm trying to read their submission. I don't want to tell people how to write to me, but if they've got a sense of humour, and they're very passionate about something then I may be more interested."

Again, the brilliant chess analyst shows a dichotomy of logic and humanity.

Which side of him does he feel is most strong?

"A bit of both may be what made me a chess player. I've always been like that. Someone asked me last night why would a mathematician chess player want to do something so beautiful as renovate a stunning Georgian building in Home House. And I was a bit disappointed with that reaction, because I think there is still a lot of room for creativity in what I do. And just because you have a logical brain, I still like to think that there's a little bit of creativity and art involved in business. As much as I would love to turn myself into a robot, there's still a lot of gut feel and there is still emotion.

Yes, I probably analyse things more than other entrepreneurs, but that helps me. It certainly doesn't stop me from doing the fun investments, but instead gives me a way of looking at things."

In our time together Farleigh's email doesn't stop with new pitches coming in every few seconds, with outstanding opportunities sure to be in there, hidden amongst the less stellar submission. But it's the good cause subject that really ignites the entrepreneur investor, his eyes lighting up at the projects he works on that make a real difference. "The more fundamental things I've been involved in, like cancer research, Alzheimer's research and asthma research, if any of these could make a significant step then that would just be absolutely fantastic, and you do that for nothing. The satisfaction in doing something like that would be valueless, priceless. So there is an excitement, but mainly because it's changing people's lives for the better, and that's what you hope."